Listen to This Episode

Episode Transcript:

Dr. Maddux: The mission of the United States Renal Data System is to document the impact of kidney disease on the US population. USRDS data support research and policy initiatives designed to improve the care of individuals living with kidney disease. One means of doing that is the publication of the annual data report, an authoritative source of data about the magnitude, characteristics, treatment, and costs of care in the United States. One important aspect of this data focuses on racial and ethnic disparities in incident and prevalent CKD and ESRD populations and their access to treatment of these conditions. Dr. Kirsten Johansen is the Director of the Coordinating Center of the United States Renal Data System. She's also chief of nephrology at Hennepin Healthcare, Professor of Medicine at the University of Minnesota and an associate editor, Editor for the Journal of the American Society of Nephrology. She joins us today for on Dialogues to discuss racial and ethnic disparities noted within the USRDS.

Welcome, Kirsten.

Dr Kirsten Johansen: Thank you.

Dr. Maddux: Just frame for everybody, the scope of the big data that you deal with, with regard to USRDS, and how it gives you the opportunity to approach looking at disparities in care?

Dr Kirsten Johansen: We're always looking to expand our data sources, but the biggest ones still remains CMS data. We get claims data, and we get the entire dialysis population data from the former CrownWeb, currently EQRS system. We use those to build our database for ESRD. In the CKD world, as you know, there isn't a real registry. We use a combination of data sources. We use claims data from CMS, but we also currently have data from Optim. We recently acquired some Medicaid data as well to try to look at some younger patients with chronic kidney disease.

Dr. Maddux: These datasets, especially CKD, and claims, datasets, have lots of opportunities to learn things, but they do sometimes miss some of the clinical elements. So, I'm wondering how you sort of manage through the need for that sort of phenotypic data, you might say, as opposed to just this transactional data?

Dr Kirsten Johansen: The optimum data set does give us some clinical data, but it's only a subset of the population. I wish we had more of that kind of data. But we have to try to get creative. What can we see with claims? What can we not? And so, every time we think about areas that we want to study, or things we want to document, the first filter is, is there a data source for that? If there isn't currently what data source might work? And could we could we get that data source at some point in the future.

Dr. Maddux: I know a lot of folks that will be watching this segment may not know what CrownWeb is, you want to just quickly just describe that for sure.

Dr Kirsten Johansen: CrownWeb was the system by which dialysis providers entered data into to eventually to reach CMS on who is receiving dialysis, what type of dialysis they're receiving, and then all the information that's necessary for CMS to administer the quality improvement program. That program, that system was phased out last year, and the new system now is called the EQRS, which stands for End Stage Renal Disease Quality Reporting System, I believe. So that one’s just come online.

Dr. Maddux: The data that you use typically, what's the vintage of that data? When you issue an annual data report? What's the timeframe you're usually studying and talking about?

Dr Kirsten Johansen: We're usually looking at a lag of about 18 months by the time because we rely so heavily on claims data by the time those claims have been have gone to CMS have been validated and all of that, and then put out as a claims file, we end up with about an 18-month delay. That's with the claim based data. The EQRS data is more up to date. We get that quarterly, and at least with regard to who's on dialysis, and what kind of dialysis we can track that a little bit more quickly. Now, in the COVID era, we felt like USRDS was the perfect place to start trying to track what was happening to the dialysis population. But we said, well, an 18-month lag... by that time, it won't be useful to anyone. So, we really work together with our NIH partners to try to get more up to date sources. Because CMS does sell more recent claims data, it's just more expensive to get it that way. So, using more recent claims data and using the EQRS data, we were able to take a look at what was going on with COVID. Not exactly in real time, but as close as we could get within the same year in 2020. We produced data on what had happened for the first half of the year.

Dr. Maddux: The pandemic sort of exposed this incredibly vulnerable population that we care for and the need for understanding what's happening almost on a week by week basis was clear to us, So, I would expect next year's ADR is going to actually have quite a bit of impression of how that changed during the course of the beginning of the pandemic. Don't you think?

Dr Kirsten Johansen: The 2020 ADR, had had some data about the impact of COVID for the first six to nine months. This year, we were able to go into even into 2021, the first half, and we already saw the evolution of the waves of COVID. We saw differences in the effect. For example, early early in the pandemic hemodialysis patients who are much more likely to get COVID to be hospitalized with COVID. And to die of COVID, than patients dialyzing at home. And even within the haemodialysis population, when we looked at those who were either recently in nursing homes, and receiving care in facilities or receiving their care in nursing homes, those patients were even higher. But that rapidly changed so that by the end of 2020, there was less of a difference. Still, hemodialysis patients were more likely, but there was less of a difference in those receiving their dialysis in nursing homes and skilled nursing facilities, were actually not that much more likely than those who were in those facilities but dialyzing in dialysis centers so that that changed during the course of the epidemic. And as people probably adjusted their infection control policies. We're still trying to tease that out.

Dr. Maddux: It was quite clear to me during this time that we were clearly seeing as the virus mutated and became, you know, changed, its fitness level as a virus, that the disease was slightly different. And the impact of vaccination then played a huge role for this patient population, and trying to at least mitigate the severity of the disease, while at the same time realizing the population still was much more vulnerable to whatever their background community, rate of infection seem to be.

Dr Kirsten Johansen: We actually did study that. And we found in 2020, and 2021, for example, we looked at hospitalization rates, and we were able to compare it to CDCs network of, I think, it's 13, or 14 states that they track. When we looked at that we saw a really strong correlation was about .9 on average between community rates and the dialysis population, but they were 40 times higher for dialysis patients. So, that's what we saw. And then to your previous question, I do think that this next year, we're going to be able to track a little bit..., the response to vaccination. And what did that do? We're going to be able to look at vaccines. We hope it's going to be tricky to know whether they're clearly documented in claims or they're not, but we're going to do our best and a very little bit we can track who received therapies for COVID as well.

Dr. Maddux: The degree of utilization of monoclonal antibodies for COVID in dialysis patients, I think, is one of the things we're talking about right now, simply because we think it was underutilized in sort of the earlier waves of this. And if we're going to practice our best mitigation steps, it's got to be some sort of active treatment with the oral drugs like Paxlovid not really being available right at this point to our population.

Dr Kirsten Johansen: So, we'll be able to catch the beginning of that, and this next year’s ADR and see what happened, and see how that compares to patients that didn't have kidney disease. To see if you're right about the underutilization.

Dr. Maddux: We'll see. We see our population of patients in general being different than the general population, certainly COVID exposed that greatly. But even within the data that you see, I'm sure there are lots of evidence areas for where the disparities of care are and where they exist and what some of the drivers of that might be. Can you speak to that for a moment?

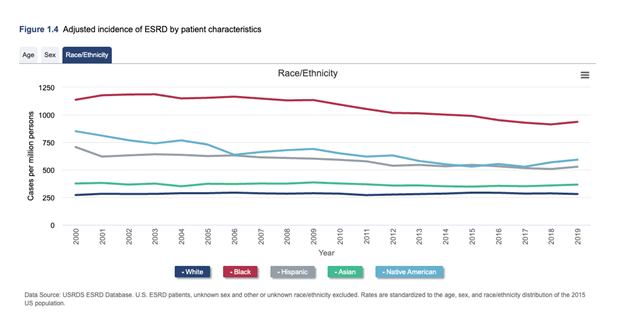

Dr Kirsten Johansen: We see disparities almost everywhere we look, unfortunately in the data. I think the one that the USRDS has been tracking for the longest since its inception in the 1980’s is the disparity in the incidence of ESRD. There has been some improvement in the disparity between black and white individuals, but it's still more than three times higher for black individuals than whites. And there is a disparity when we look earlier in CKD, we use another source of data that I didn't mention earlier, was in NHANES data than National Nutrition and Examination Survey. That is a population designed to be representative of the US population. And when we look at that we can, actually ascertain who, who really has evidence of kidney disease. We only do one measure of EGFR, not two in that survey., they only do, but in any case, when we look at that, we don't see such large differences in the prevalence of CKD between black and white people, it's a little bit higher. And now of course, there people are changing equations. It depends on the equation, but it's somewhere between maybe 20 to 60%, higher, when you talk about CKD stages, three through five, not three-fold higher. So, something's going on between getting CKD and getting to end stage kidney disease. And that's something we wanted to try to delve into more in this year's ADR.

Dr. Maddux: I think that'll be helpful, because it could be everything from well, the types of kidney disease could change the rate of progression and the course the access to new medications that may mitigate some of that disease, the access to the health care system, in general. I mean, all of those are, seemed to me to be things if those could be untangled with some of the analyses that you all do. That would be extremely useful.

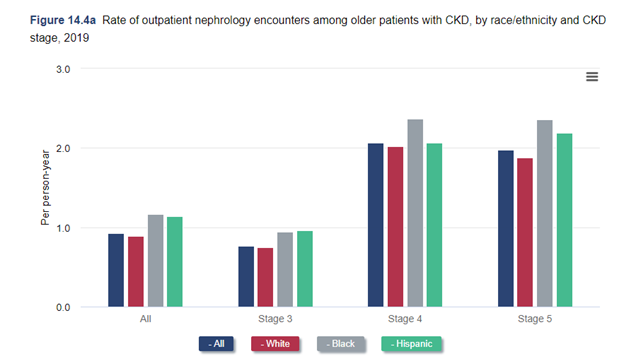

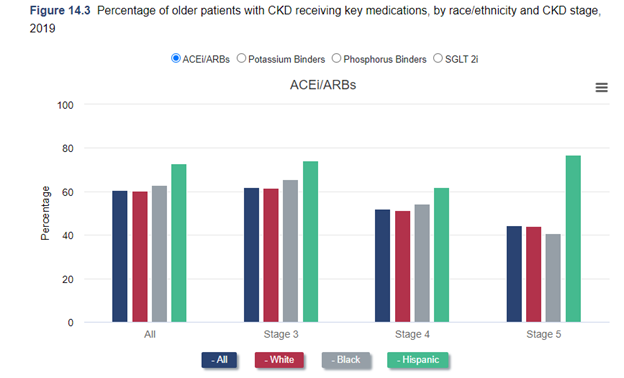

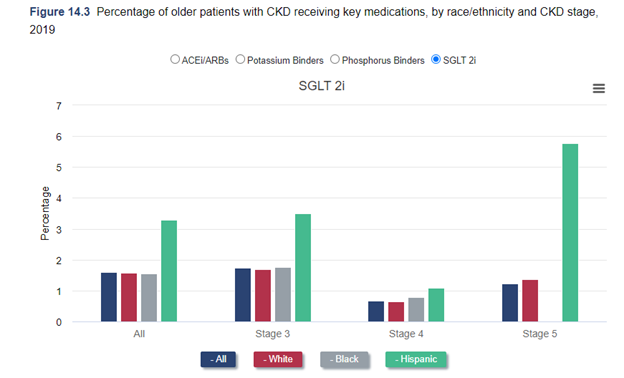

Dr Kirsten Johansen: As we were discussing before, we always have to think about the limitations of our data. So, we actually looked at that last year. We looked at among Medicare beneficiaries who are over 65. We looked at nephrology visits among people with CKD. And we looked at use of ACE inhibitors and ARB's with the SGLT2 inhibitors, other medications. We actually found no disparity at all, we found no difference between black, white, and Hispanic individuals in that. But you really have to think about that. That's among Medicare beneficiaries over age 65. They have good access to care. And so that's a success in a way. But I think that if you just said: well, there's no problem, you would really be missing a huge issue, because problem is younger patients. Oftentimes, black and Hispanic patients are getting kidney disease at younger ages before they qualify for Medicare. And so, we can't see that if we use Medicare data. So This year, we're going to use Medicaid data to try to address that. Of course, that comes with its challenges. Medicaid differs state to state. And in fact, data on race and ethnicity and Medicaid varies state

to state, some states don't report it at all. And some states report it for a minority of the patients. So, we're having to be very thoughtful about what group of states we think we can study. But I think we'll be able to cover at least a good deal of the country and try to look at that and whether there are differences in that population, because I suspect that we may find them.

Dr. Maddux: Going back to your comment about incidence of kidney disease and recognizing that the proportion of population groups that have disparate results in incidence of kidney disease, I'm sure extends not only to black Americans, but also Hispanics. The question of Native Americans and others... I'm curious whether there's enough data to really make any kinds of conclusions about other populations in sort of a more granular way?

Dr Kirsten Johansen: We actually did focus on black and Hispanic individuals in our disparity supplement that we produced,

because we ran into that if we try to subdivide and adjust for other factors like age and socioeconomic status and neighborhood characteristics, the groups become so small that it really is difficult to come to clear conclusions about those groups. In general, though, when we take the population as a whole, we know that they're very high in those groups as well. Although also the Native American population, there's been really great progress, and I know you're going to ask me about policies and this is one that the government I think, is really quite proud of. So, I'll jump ahead to that. You know, In 1997, they put forth an initiative to address diabetes in the American Indian population. And that included things like better education about diabetes, special clinics to take care of it, care teams, access to nutritionists, dietary information, all sorts of things. and the incidence of diabetes and actually, of end stage kidney disease has really declined in that population in the last two decades. It's impossible to say whether it's absolutely because of that, but it seems likely.

Dr. Maddux: I think of some of the variability that I see in transplant as being another area that could use quite a bit of focus and access to organs, organ availability, and transplant as an option and a modality for ESKD care.

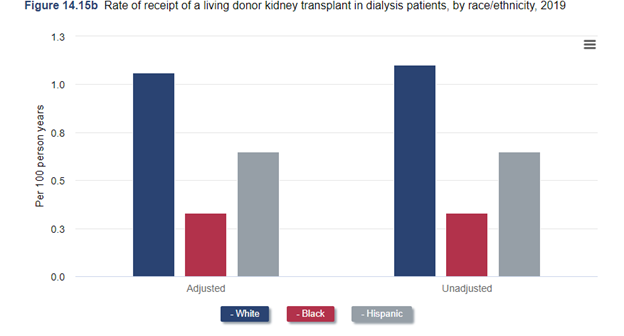

Dr Kirsten Johansen: That's one area where even having Medicare and full medical care has not fixed the problem. The change in the kidney allocation system that happened in 2014, does look like it improved things a little bit, at least for black patients, the difference between black and white in terms of deceased donor access improved. But you have to really be careful about that as with everything else, because that's among people who are already on dialysis. First of all, access to pre-emptive transplant is still lower in most groups other than non-Hispanic whites. But once you're on dialysis, access has improved. I think that still masks ongoing disparities, because that's sort of unadjusted rates if you just look, but our black patients tend to actually be a little bit younger, a little bit healthier. And when you start to account for who's actually eligible for a transplant, I think they widen back out again, a little bit actually. But there's been some progress on that.

Dr. Maddux: In many cases, there may be drivers that are social, environmental, cultural, local, communities, how they perceive. So, for example, if there are fewer living donor opportunities in the black community, then because there is a cultural impasse in some way, then that creates an opportunity for us to look at what are the actual drivers that might actually be leading to the result that you described. These are the kinds of things that we need to begin to uncover from some of the data like the data that you've shown so that we can figure out what is it that might change the minds of people or change the conditions under which the disparity actually exists.

Dr Kirsten Johansen: I think the donor issue is particularly thorny, and I I'm not a transplant nephrologist, as you well know, but looking at it from the dialysis perspective, as you're saying, it's a big concern.

There is a slightly higher risk, even though the risk overall is still low – higher risk of a of a black organ donor going on later to have kidney disease and even to potentially require dialysis. So, there's appropriate concern about screening and safety of donors on the one hand, but on the other hand, if that is applied too stringently are we rejecting donors, and then worsening this disparity in access to living donation that we see because that one even though we didn't really talk about it a minute ago very much, is still very much there. Hasn’t really changed a lot. There’s a big difference in rates of living donor kidney transplantation among white and black recipients. So, that’s something we really do need to fix. But, we have to do that without risking the health of donors. It’s something that I think transplant centers are really struggling with.

Dr. Maddux: What other social determinant factors do you think are on the verge of having sort of higher profile in our discussions nationally?

Dr Kirsten Johansen: I see social determinants of health discussed more and more. It seems like you know, that's our, our social, environmental, and structural factors that affect people's care, but aren't necessarily medical things like the neighborhoods that they live in, what the socioeconomic status is in that neighborhood education levels of the people who live there. And that's something we tried to delve into a little bit too with the USRDS data. We can look at those neighborhood characteristics, and we can look at also crowding of housing and, and things like that. We did that to try to tease out some, especially the disparities in access to living donor transplantation and also to home dialysis, which we haven't touched on yet. Another topic that I know is very important to you and to the nephrology community, those disparities are there. We found that they are pretty highly associated with those neighborhood characteristics. So, neighborhoods that have more deprivation on this index that takes into account a number of those factors. People who live in those neighborhoods are less likely to be treated with home dialysis or to receive a living donor kidney transplant.

Dr. Maddux: To what degree do you think the infrastructure of our kidney disease care system today is so highly developed for in-center care but not well developed for home care, that we need to sort of expose to policymakers and others that there are opportunities to make sure the infrastructure for homecare is as developed as we've made it over 50 years now for in-center care.

Dr Kirsten Johansen: Two big barriers that I think we need to address for home dialysis, are people with low functional status, how to make it more accessible to them, and people who live in apartments or smaller or more crowded environments. How can we address that? So, you know, In Canada and other places, sometimes they pay nurses or partners for people to come help people set up their dialysis, but that's not something that we do in the US. We could do that. And if someone gets placed into a long-term nursing home facility, most of those facilities cannot do peritoneal dialysis. So, if we're going to try to expand peritoneal dialysis, we need to find a way to provide it not just based in-centers, but in other places as well. And then in terms of the living situations, I don't know why we're so stuck on supplies need to be delivered once a month? Why can't we deliver supplies every week or every two weeks so that people can actually find room to store the supply?

Dr. Maddux: The logistics, the ability to create systems where fluid generation can occur on-site?

Dr Kirsten Johansen: That's another possible solution.

Dr Maddux: A huge solution to one problem. But, It also strikes me that just calling it home dialysis creates one of the biases that we have, because the immediate assumption is that that geography is your own home. But if we had people doing effectively self-care in a setting that was near their home, but maybe in an environment that was better than the actual apartment they live in, or the place that they actually are. There may be a way to achieve a little bit of both – not a formal health care facility. But a place where a home treatment could be delivered, but not in the physical place of your home.

Dr Kirsten Johansen: Could you imagine people picking up their supplies every couple of days or something?

Dr Maddux: Picking up their supplies or dropping into the local community home center. Whatever you'd call it. I don't know what you would call it. But a place where people socialize there with others that are having to go through the same experience and helping each other a little bit but still doing their own care.

Dr Kirsten Johansen: Well, I think that would be great, because I have had some patients who have had to temporarily switch into hemodialysis from home dialysis or something. And I've had and I'm sure you've seen the occasional patient who decides they want to stay on dialysis, because now they found a community of patients that they hadn't had at home. So that would also provide that.

Dr Maddux: I think there are more than a few people that do dialyze mostly in-center today that get a lot of positive socialization with that and avoid some of the loneliness they may have.

Dr Kirsten Johansen: I think subtly, there's also another socio economic message in there maybe.

Dr Maddux: I think the message of what's an acceptable location to be able to do this and where somebody lives, that can do this creates a huge problem if people have to have a certain type of home. Today, because of all the boxes and bags of fluid and other things - machinery that we have, there's some requirement that there be enough space for that. If I were to look out in the future, I would hope we would see things like online fluid generation for either home, hemo or PD. We would create environments where people could either do these treatments in their own home or have a drop in place that's in their sphere of environment that would allow them to do it in a place of reasonable comfort and safety. And this whole socialization issue, I think, becomes an interesting component to this where maybe two or three people with like interests want to do this at the same time together. And that gives them a bit of community.

Dr Kirsten Johansen: Right. I think that community aspect is really interesting to be able to bring that to home dialysis, or whatever we decide to call it in the future when we when we get there. How much of a problem do you think there is on the provider side? In terms of thinking, is this a patient who's appropriate for home dialysis? Because I think we underestimate who can do home dialysis.

Dr Maddux: I agree with you. I think we underestimate who can participate in their care in any way, whether it's in-center, home, hemo or PD. I think today, on the provider side, I'm sure we are cautious, overly cautious, at times in the people in the conditions that we think are acceptable for home dialysis. Because this grew out of trying to make sure there was extreme care in trying to provide what was needed there so that we need to make sure we have more flexibility in the infrastructure. That's not just the providers. It's the payment system. It's the support systems from the government. It's the relief for family members or associated caregivers that need to assist, but are not licensed and credentialed. All of those things need to be worked on in a way to create the right environment to truly stimulate the degree to which home could potentially penetrate, the overall population of patients. And then we need to make sure we don't exclude the fact that transplantation is the number one home dialysis therapy. No question and it can't live in another world,

Dr Kirsten Johansen: Which it does right now to

Dr Maddux: The island of transplant, in my mind, needs to be brought into the center of kidney care somewhat more.

Dr Kirsten Johansen: Do you think any of these new care models in which dialysis organizations can potentially partner with transplant centers and with nephrology practices, do you see any potential to improve that?

Dr Maddux: I think it offers opportunity for novel methods of modality to be developed and to realize that a patient's journey through their lives is going to go through a lot of different modalities. Some of those modalities will be highly intercalated with each other based on the dynamics even in a given year or month that a patient may need to be a home patient, but they need to go in-center for a couple of weeks because they need respite care. Or they've had an upper respiratory infection, and they need a little more attention than they can provide themselves. We don't have a flexible environment today. We've got an environment that kind of rigidly puts you into the modality sphere that's been that you've selected or has been selected for you. I think the infrastructure of all of the systems, whether it's our lab systems, our provider systems, our payment systems, our transportation systems our social support systems, all those need to be looked at holistically to really get people more engaged in participating in the provision of their care. All these things need to get some adjustments or some recognition. Value-based care programs that we have, I think, offer the opportunity to think more creatively than we've been able to before. And to realize also that this isn't just about renal replacement therapy at end stage kidney disease, it begins many years for most patients before that, at stage two and stage three CKD, when you could intervene and change the course of that lifetime journey. I think we think too transactionally about this slice of today's time.

Dr Kirsten Johansen: We do it in the clinical world, and we do it in the research world, too. I hope we can change this. I think maybe we are, but we've always thought: well, this person studies acute kidney injury, and that person studies chronic kidney disease, and that person studies end-stage renal disease and transplant, and these are all stages and things that happen to people.

Dr Maddux: It would be wonderful for USRDS, if you were able to have enough longitudinal data that could get down to tracking patients journeys, look at modality changes and what's actually required, because, what frightens me the most, is the transplant patient coming back to whatever form of dialysis have horrible outcomes.

Dr Kirsten Johansen: That word is one of our words, journeys. And it's one of the words that we and NIDDK and our Board want to try to focus on a little bit more. And we are struggling a little bit with how to present that in a way that is digestible, because there are a lot of different stages. One can think about a diagram and people go here and there, and it becomes quite complicated. We are doing some of that trying to look at a little bit more what happens when people switch from home to in-center dialysis. What does happen after a transplant fails? So, we're doing more of that in this year's annual data report.

Dr Maddux: One of the things that's interested us, that we've begun trying to track internally, is how many times do we have a home hemo patient switch to PD, or PD patient switch to home hemo not in-center, simply because they want to stay at home. They want to stay engaged and independent in that care. I'm a fairly strong believer that there are many patients that are ill enough that their care is relatively passive it's provided to them. But there are many, many more patients who could be much more active participants in their care and the benefit of that emotionally for them and in the quality of life that they have. I just in my gut feel that there's a big opportunity there.

Dr Kirsten Johansen: I agree with you. And for the most part, that's what we do. When they're in advanced chronic kidney disease, as you say, not everyone is in a place where they can do that. But with most of our patients, that's what's happening. So why, then, when they transition to dialysis do we expect them to just sit in a chair and receive dialysis and not ask any questions and not participate? It doesn't make any sense.

Dr Maddux: For the first 50 years of this program, we had built almost an ideal system to make sure everybody could get access to a life-saving treatment.

Dr Kirsten Johansen: That's right.

Dr Maddux: Pre-COVID, we've optimized continual improvement, observation ways to look at that. But I think when we think of the lifetime journey of that patient, and we realize they go in and out of all kinds of waves of, of need, and activity as their life changes during this time. I don't know that we've thought about it nearly as holistically that those various modalities are really just one. It is just the care of the individual. And that's where I think the challenge is for us, as the renal community, is to figure out how do we make that, we're part and parcel of what the expectation is that we're going to realize people will change through all these different phases. And that last phase being that there's a point in time where truly end of life, conservative care can be done and choreographed in a way that's much better for the healthcare system, but a whole lot better for the family and the individual themselves.

Dr Kirsten Johansen: that's a big need. You're right.

Dr Maddux: When you look at USRDS, and I know that you look at registries and data from other countries and so forth, one of the things we're doing in our global medical office is trying to look at how do we understand kidney disease care in the various countries around the world? What's the base state there hoping that in all parts of the world, there'll be some similar registry function, or ability to try to understand how is kidney disease not only cared for, but perceived by the political environment and the government environment, the payer environment and the population. Do you see there being any improvement in the ability of peer registries around the world to really get to the heart of what it looks like in their own countries?

Dr Kirsten Johansen: We're very fortunate to receive data from countries all over the world that we include in our international section of the annual data report. We can certainly track differences in incidence and prevalence, and we look at modality and a little bit at transplantation. We see huge variations in these things across the world. We struggle with this as well. What should be the scope of a registry? Is it just to monitor the incidence and the prevalence and those things? Which is what a lot of registries do. Or should it be a little bit more proactive forward looking towards, what could we document that might help highlight a problem or lead to some policy change? And where is that line? And how much is too much? That's something we struggle with every day at USRDS.

Dr Maddux: I think we have a great interest, we've set up with Dr. Dalrymple, population health and medicine group, to try to take the 23 largest countries, we're somewhere in that range, that we work in from a service delivery side and say what do we actually know about what kidney care looks like in that country? What's the life of the kidney patient look like in those countries, how do we look at it not just from pathophysiology, medical point of view, but from a more holistic view, and recognizing that if we could generate interest in those countries, to emulate something like the USRDS as a way to not only observe what's happening, but use that as a tool that you and I both know Dr. Collins did for years to say, "here's a policy direction that should be strongly considered." That's of great interest to us. The example that your group setting is really what stimulated this.

Dr Kirsten Johansen: Well, that's great. I think I also have just for years really admired the DOPPS study. That was set up with that type of function in mind. They've taught us a lot about how practice varies across the world. So that's another parallel and very interesting and important work that’s going on.

Dr Maddux: It's been a little bit unusual for me this year. We've now got a new set of drugs that are both cardio-protective, mitigate the progression of CKD have now been approved for both diabetics and non-diabetic patients. And yet, our rate of utilization is like tiny, just tiny, the SGLT2 inhibitors. It's been very, very slow to take hold in the renal community.

Dr Kirsten Johansen: That's not my local experience. But that's something that we're also looking at a little bit at least with home dialysis, is these differences, geographically, areas of uptake in areas that are lacking is I think something very important to look at.

Dr Maddux: The degree to which, out in the communities that we've seen uptake in earlier stage CKD with SGLT2s has been a lot less than we expected.

Dr Kirsten Johansen: I know one thing I've seen is, at least initially, was some hesitation about who owns that. Is it endocrinologist? Is it nephrologists?

Dr Maddux: Isn’t that part of the problem now, there has to be an owner when in fact, you could call cardiology, endocrine, or nephrology the owner of these drugs….

Dr Kirsten Johansen: Exactly. In my group, we nephrologists are pretty aggressive about it. We've decided we own it.

Dr Maddux: That's good. I would like you to promote that to our colleagues around the country, that would be really useful.

Dr Kirsten Johansen: That's our very strong feeling.

Dr Maddux: If I look to date at the degree to which nephrologists have really taken hold of this, it's not as many as I would have expected.

Dr Kirsten Johansen: That's disappointing, because I feel like we should. You often have to change diuretic dosing or other antihypertensives, and that's right in our wheelhouse. I feel we should be doing it.

Dr Maddux: Before we end, any final comments on what you see going forward with USRDS and your interests in this combination of health equity, disparities, and social determinants of health care?

Dr Kirsten Johansen: I know none of us has our crystal ball to know what's really going to happen with COVID, but I really think that we need to transition from just documenting what a terrible impact it's had on the population in terms of mortality and move towards treatment. And make sure that we advocate for our patients to get treatment for COVID, if it continues to be a problem because patients with kidney disease are often left out of clinical trials. Then we're left to wonder whether these drugs are okay. So, we need to make sure they get included in those trials, and they get treated as they need to be treated. I think it's going to be really important as these new payment models have been coming online, to try to incentivize more home dialysis, that we really monitor that, monitor how that happens. Are they successful in actually doing that? But beyond that, as we've been talking today, do we address these disparities that we know are there? Do we close these gaps? If we're able to increase home dialysis? Or do we just increase it in the people who already had more access? It's going to be very important, I think, for us to track that so that policymakers can look at that and decide whether there needs to be any change in these policies or not. So, I really view our role as trying to make sure that we think about how to monitor the effects of things that happen so that if they need to be iterated, that can happen.

Dr Maddux: Thank you. I've been here today with Dr. Kirsten Johansen. She's director of the coordinating center for the United States Renal Data System. Fascinating conversation today. Thanks so much for joining me, Kirsten.

Dr Kirsten Johansen: Thanks, Frank. I enjoyed it, too.